D’Arcy Vicknair founding partner, Adrian D’Arcy, along with Special Counsel, Ashley Robinson, co-authored an article titled “Sureties and Pay-If-Paid Clauses: Balancing Subcontractor Protection with Freedom to Contract” for the American Bar Association’s Tort Trial and Insurance Practice Section’s magazine, The Brief. Adrian and Ashley used their collective expertise in the field of surety law to delve into pay-if-paid clauses.

D’Arcy Vicknair founding partner, Adrian D’Arcy, along with Special Counsel, Ashley Robinson, co-authored an article titled “Sureties and Pay-If-Paid Clauses: Balancing Subcontractor Protection with Freedom to Contract” for the American Bar Association’s Tort Trial and Insurance Practice Section’s magazine, The Brief. Adrian and Ashley used their collective expertise in the field of surety law to delve into pay-if-paid clauses.

Sureties and Pay-If-Paid Clauses: Balancing Subcontractor Protection with Freedom to Contract

There is a long history of public entities mandating surety bonds for public construction projects to protect taxpayer dollars and provide financial security to the downstream subcontractors and suppliers. Quite often these public policies of protecting taxpayer dollars and lower-tier subcontractors and suppliers are incongruous with the parties’ freedom to contract. The surety and construction industries rely heavily on the freedom to contract to shift the risk of nonpayment by the owner from general contractors to lower-tier subcontractors and suppliers through contingent payment or “pay-if-paid” clauses.

The competing public policies of protecting lower-tier subcontractors and suppliers and allowing parties the freedom to contract are at the forefront of legislative debate and judicial consideration. Whether general contractors can rely on pay-if-paid clauses to avoid paying subcontractors and suppliers until after the general contractor receives payment from the owner and whether sureties can likewise rely on pay-if-paid clauses to avoid payment claims from subcontractors and suppliers are the pertinent issues. And, whether a state legislature is debating the latest bill on pay-if-paid defenses or a court is examining a surety’s pay-if-paid defense in the absence of a legislative decision, there are two main considerations: (1) the clear importance of freedom to contract as part of “the framework of modern commercial life,” and (2) the public policy against pay-if-paid clauses because of their impact on mechanic’s lien rights and a subcontractor’s claim for payment for work performed. [1]

Over the last few years, new case law and state legislation have changed whether pay-if-paid clauses are enforceable and whether sureties can rely on these clauses. This article explores the most recent state legislation and case law on pay-if-paid clauses, the enforceability of pay-if-paid clauses over the 50 states, and whether sureties can rely on those clauses.

Contractor’s Freedom to Shift Risk of Nonpayment Through Pay-If-Paid Clauses

It’s no secret that the construction industry customarily “places the risk of an owner’s insolvency on the general contractor.”[2] Most successful general contractors are not novices to the risks involved in the construction industry and proactively use their freedom to contract to shift the risk of owner insolvency to their downstream subcontractors and suppliers. General contractors shift this risk by including conditional payment clauses or pay-if-paid clauses in their subcontracts. A pay-if-paid clause “means that a subcontractor gets paid by the general contractor only if the owner pays the general contractor for that subcontractor’s work.”[3] In other words, the general contractor’s “receipt of payment is a condition precedent to its obligation to pay [the subcontractor].”[4] General contractors usually have the higher negotiating power to require subcontractors to assume the risk of nonpayment through pay-if-paid clauses.

The contractual language necessary to create a pay-if-paid clause varies by state, but generally no specific language is required.[5] A pay-if-paid clause is created “as long as the contract on its face contains clear and unequivocal language that unambiguously sets forth the parties’ intention and agreement that owner payment is a condition precedent to the general contractor’s obligation to pay the subcontractor.”[6] “A typical ‘pay-if-paid’ clause might read: ‘Contractor’s receipt of payment from the owner is a condition precedent to contractor’s obligation to make payment to the subcontractor; the subcontractor expressly assumes the risk of the owner’s nonpayment and the subcontract price includes this risk.’”[7]

While a pay-if-paid clause shifts the risk of nonpayment to the downstream subcontractors and suppliers, it should not be confused with a pay-when-paid clause, which does not shift the risk of nonpayment to subcontractors. Unlike a pay-if-paid clause, “[a] pay-when-paid clause governs the timing of a contractor’s payment obligation to the subcontractor, usually by indicating that the subcontractor will be paid within some fixed time period after the contractor itself is paid by the property owner.”[8] Pay-when-paid clauses “address the timing of payment,” whereas pay-if-paid clauses address “the obligation to pay.”[9] For example, “[a] typical ‘pay-when-paid’ clause might read: ‘Contractor shall pay subcontractor within seven days of contractor’s receipt of payment from the owner.’”[10] Under pay-when-paid clauses, the general contractor will remain liable to the subcontractor if it fails to receive payment from the owner.

Contractor’s Freedom to Shift Risk Is Not Wholly Unfettered

A leading construction law treatise suggests that there is nothing inherently unfair about a pay-if-paid clause that operates to shift the risk of nonpayment by the owner to the subcontractor because the subcontractor can figure this into its price.[11] In most states, courts have held that in the absence of legislation preventing the enforcement of pay-if-paid provisions, the judiciary will enforce pay-if-paid clauses as long as the contract language is clear and unambiguous as to the agreement of the parties to shift the risk of nonpayment.

Several states have enacted legislation to declare pay-if-paid provisions unenforceable because they are against the public policy of protecting the lower-tier subcontractors and suppliers from the risk of nonpayment. This public policy of protecting the lower-tier parties is usually expressed in public works statutes, which grant the lower-tier subcontractors and suppliers rights to preserve their claims for nonpayment outside of their contract with the general contractor, such as the right to file a lien on the project or the right to assert a claim against the statutorily mandated payment bond for the project. These public policy protections under most public works statutes often conflict with the parties’ freedom to contract and shift risk to lower-tier subcontractors and suppliers.[12] In the states that have enacted legislation declaring pay-if-paid provisions unenforceable, the legislature has determined that the public policy benefit of protecting lower-tier parties is greater than the desire to allow parties the freedom to contract and shift risk.[13]

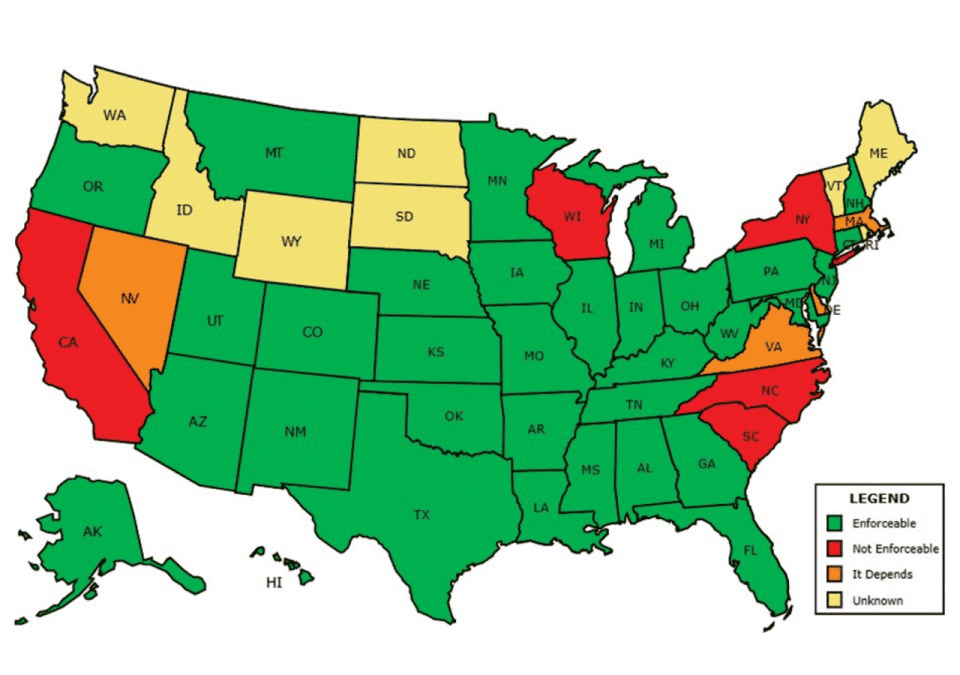

As depicted in figure 1,[14] most states in the United States enforce pay-if-paid clauses and allow parties to freely contract to shift the risk of nonpayment downstream. However, five states have definitively made pay-if-paid clauses unenforceable: California,[15] New York,[16] North Carolina,[17] South Carolina,[18] and Wisconsin.[19]

Until recently, Nevada was included in this list of states that made pay-if-paid clauses unenforceable, but in recent case law, the Nevada Supreme Court confirmed that pay-if-paid provisions are not per se void and unenforceable as long as they do not violate rights or obligations under certain statutes.[20] Therefore, Nevada is depicted in figure 1 as an “It Depends” state.

The most recent state to declare pay-if-paid clauses unenforceable is Virginia.[21] Under Virginia’s legislation, pay-if-paid clauses in contracts entered into after January 1, 2023, are unenforceable as against public policy on both private and public construction projects. However, in figure 1, Virginia is identified as an “It Depends” state because pay-if-paid clauses in contracts executed before January 1, 2023, are still enforceable. There is also an exception under the private works statute that allows pay-if-paid provisions to be enforceable if the party contracting with the contractor is insolvent or a debtor in bankruptcy. Under these new Virginia laws, contractors are required to make downstream payments to their subcontractors within the earlier of seven days after receiving payment from the project owner or higher-tier contractor or 60 days after satisfactory completion of the work for which the subcontractor issued an invoice, regardless of whether the payment is received from the owner or higher-tier contractor. Upon enactment, these changes immediately started impacting how contracts in Virginia were being drafted and negotiated.

Only two other states are identified as “It Depends” in figure 1: Massachusetts and Delaware. In Massachusetts, pay-if-paid clauses that do not fall under the Massachusetts Prompt Pay Act are enforceable, but pay-if-paid clauses that do fall under the act are unenforceable.[22] In Delaware, pay-if-paid clauses on private construction contracts are void and unenforceable.[23] However, the Delaware state legislature and the state and federal courts have not considered the enforceability of pay-if-paid clauses on public projects.

Because the enforceability of pay-if-paid clauses may depend on the law in effect when the contract was executed, whether the project is public or private, and whether the project meets certain criteria, practitioners must carefully consider the applicable statutes, case law, and exceptions that govern each pay-if-paid clause as issues arise.

Risk Shifting to Sureties on Public Projects

Surety bonds have been essential tools in public construction projects for over a century. By mandating that a general contractor provide statutory surety payment bonds, public entities are insulated from the risk of contractor default or nonpayment. These statutory payment bonds transfer the risk of the contractor’s default and nonpayment to the surety company.

The federal government, nearly 50 states, and most local jurisdictions have enacted similar legislation to require statutory surety bonds on public projects of a certain size. These statutory surety bonds and their interpretation are shaped, molded, and restricted by the statutes mandating them and the public policy considerations that are the foundation of the statutes themselves. The statutes requiring surety bonds on public projects often restrict the general contractor’s and the surety’s freedom to contract and the terms and provisions that may be included in a bond. Statutory surety bonds generally mean that statutorily required terms must be read into the bond and any term outside of the statute will be disallowed or read out of the bond. This is often referred to as the “read-in, read-out rule.” Under the read-in, read-out rule, the statutory bond will not be allowed to enlarge or diminish the conditions required by the statute.

While the use of statutory surety bonds on public projects is mandated, the use of surety bonds on private construction projects is often discretionary, so the parties are free to contract without limitations. Generally, surety bonds on private projects will not be restricted by all the public policy considerations imposed on public projects. However, surety bonds on private projects often serve the same purpose—to shift the risk of the general contractor’s default or nonpayment to the surety company.

Surety Defenses and Pay-If-Paid Clauses

While the risk of nonpayment is shifted from the owner to the surety company through the payment bond, the surety is not defenseless. A fundamental tenet of suretyship is that “a surety’s liability is derivative [of its principal] and defenses available to the principal are available to the surety.”[24] Thus, a surety can only be held liable under the bond to the extent that the principal could be held liable.

Therefore, when evaluating a claim of nonpayment by a lower-tier subcontractor or supplier, the surety typically will look to the principal’s defenses under the principal’s subcontract. One of the most common principal defenses is the pay-if-paid defense based on a conditional payment clause in the contract between the general contractor and the subcontractor.

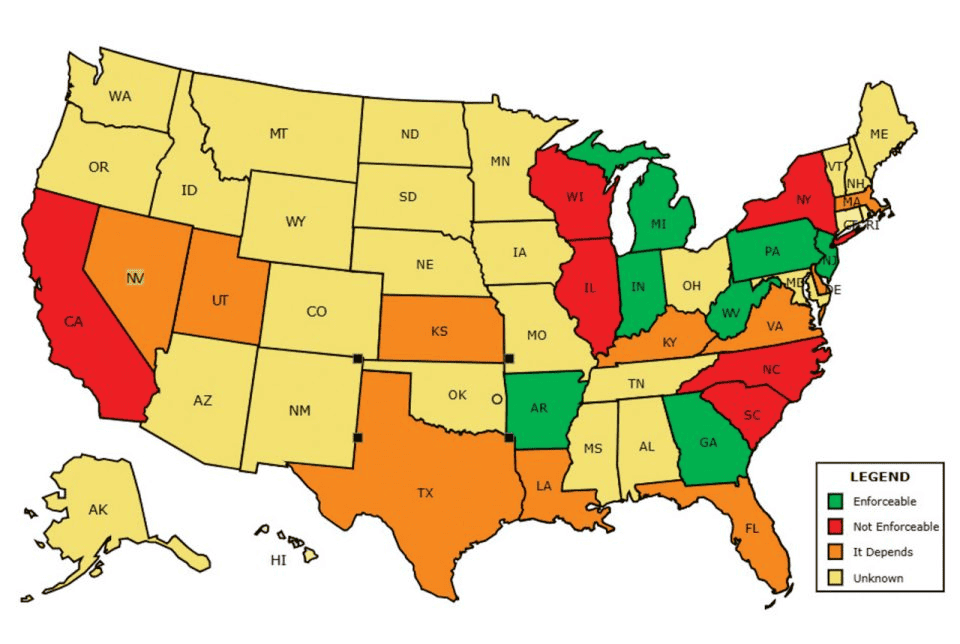

Following the basic rules of suretyship, if the pay-if-paid defense is available to the general contractor, then it should be available to the surety as well because the surety is standing in the shoes of its principal. While this is the logical conclusion, only seven states currently allow a surety to enforce a pay-if-paid defense: Arkansas,[25] Georgia,[26] Indiana,[27] Michigan,[28] New Jersey,[29] Pennsylvania,[30] and West Virginia[31] (as depicted in figure 2).

In some states, whether a surety can enforce a pay-if-paid defense depends on whether it is a private or public project, whether the bond incorporates the contract pay-if-paid provision, and when the law went into effect. Those states have been marked as “It Depends” states in figure 2. In the majority of states, it is still unknown whether a surety can rely on the pay-if-paid defense because there are no cases addressing the issue.

However, six states have addressed the issue and prevented a surety from relying on a pay-if-paid defense: California,[32] Illinois,[33] New York,[34] North Carolina,[35] South Carolina,[36] and Wisconsin.[37] These states are marked as “Not Enforceable” states in figure 2. Given the recent change in Virginia law, sureties in Virginia will no longer be able to enforce the pay-if-paid defense to payment bond claims. However, Virginia is listed as an “It Depends” state because for any contract entered into before January 1, 2023, pay-if-paid clauses are still enforceable, and prior to the recent change in the law, sureties were allowed to enforce pay-if-paid clauses as a defense to a payment claim.

Recent Change in Surety’s Ability to Enforce Pay-If-Paid Clauses in Louisiana

In its 2024 legislative session, Louisiana enacted changes to its public works statutes to specifically allow a surety to assert “any defense to the principal obligation that its principal could assert except lack of capacity or discharge in bankruptcy of the principal obligor.”[38] In doing so, the Louisiana legislature sought to legislatively overturn long-standing Louisiana case law that prevented a surety from asserting a pay-if-paid provision in its principal’s contract as a defense to the subcontractor’s claim for unpaid materials.[39]

Prior Louisiana case law on this issue weighed the public policy concerns of protecting lower-tier subcontractors and suppliers from the risk of nonpayment and found that allowing a surety to assert a pay-if-paid provision as a defense to paying a subcontractor’s claims for unpaid materials would render the protections afforded suppliers under the Louisiana lien law applicable to public projects meaningless.[40] These protections included the right to bring a claim against the payment bond surety in the event that the general contractor did not pay the supplier. Under the new Louisiana legislation, statutory payment bond sureties on public works projects are now able to assert the defenses of their principals, including pay-if-paid clauses.

Legislation Preventing Waiver of Lien Rights

Louisiana is not the only state that has debated the public policy considerations of protecting lower-tier subcontractors and suppliers and allowing parties the ability to freely contract. In several states where pay-if-paid clauses are enforceable between the parties to the contract, the state legislature has declared void and unenforceable any contractual provision that requires a lower-tier subcontractor to waive its right to a mechanic’s lien or to a claim against a payment bond before payment has been made (anti-waiver statutes).[41]

These particular anti-waiver statutes clearly state that a pay-if-paid clause cannot be used to invalidate or prevent a subcontractor from filing a lien on a project or a claim against the surety. However, many of the anti-waiver statutes, including the ones cited above, are written ambiguously as to what effect, if any, they may have on the surety’s liability and whether the prohibition against waiving lien rights means that a surety cannot assert its principal’s pay-if-paid defense. Absent case law in each of these states specifically addressing the anti-waiver statute and whether the surety can enforce the pay-if-paid clause as a defense to payment, it is unclear how courts will rule on this issue.

For instance, Montana Code section 28-2-723 states that “[a] construction contract may not contain provisions requiring a contractor, subcontractor, or material supplier to waive the right to a construction lien or a right to a claim against a payment bond before the contractor, subcontractor, or material supplier has been paid.” Until a Montana court interprets this statute, it is unclear whether this statute preventing the waiver of a right to file a lien or bring a claim against the surety bond can be interpreted to also prevent a surety from asserting the pay-if-paid defense. Seemingly, under the general rules of suretyship, nothing in this statute prevents the surety from enforcing the principal’s pay-if-paid provision. However, some courts have opined that allowing a surety to enforce a pay-if-paid provision as a defense to a payment bond claim is “an impermissible indirect waiver or forfeiture of the subcontractor’s constitutionally protected mechanic’s lien rights in the event of nonpayment by the owner.”[42]

In New Jersey, the legislature enacted a similar anti-waiver statute, which provides that “[w]aivers of construction lien rights are against public policy, unlawful, and void, unless given in consideration for payment for the work, services, materials or equipment provided or to be provided, and such waivers shall be effective only upon and to the extent that such payment is actually received.”[43] In interpreting this anti-waiver statute, a New Jersey court debated both the public policy considerations of allowing parties to freely contract and the need to protect lower-tier subcontractors.[44] Ultimately, the court found that the anti-waiver statute did not invalidate the conditional payment clause on public policy grounds and did not prevent the surety from using the conditional payment clause as a defense against the subcontractor’s claim against the surety bond.[45]

Until the legislatures in these anti-waiver states clarify the surety’s ability to assert the pay-if-paid defense or the judiciary interprets these statutes, the question of whether sureties can assert the pay-if-paid defense will remain “Unknown,” as shown in figure 2.

Balancing Public Policies in Construction Payment Law

The competing public policies of (1) freedom to contract for the purpose of shifting risk on a construction project and (2) protecting downstream subcontractors and suppliers from nonpayment will continue to be at the forefront of legislative changes and judicial considerations in this continually evolving industry. As shown by the recent legislative changes in Virginia and Louisiana, the practicing lawyer must continually stay informed about this ever-changing area of the law.

[1] JPC Merger Sub LLC v. Tricon Enters., Inc., 286 A.3d 1186 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. 2022).

[2] Sloan & Co. v. Liberty Mut. Ins. Co., 653 F.3d 175, 184 (3d Cir. 2011).

[3] Id. at 179.

[4] BMD Contractors, Inc v. Fid. & Deposit Co. of Md., 679 F.3d 643, 649 (7th Cir. 2012).

[5] Fixture Specialists, Inc. v. Glob. Constr., LLC, No. 07-5614(FLW), 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 27015, at *14 (D.N.J. Mar. 30, 2009).

[6] JPC Merger Sub, 286 A.3d at 1197.

[7] MidAmerica Constr. Mgmt., Inc. v. Mastec N. Am., Inc., 436 F.3d 1257, 1261–62 (10th Cir. 2006).

[8] BMD Contractors, 679 F.3d at 648–49.

[9] Id. at 649.

[10] MidAmerica Constr. Mgmt., 436 F.3d at 1261–62.

[11] 2 Steven G.M. Stein, Construction Law ¶ 7.04 (Matthew Bender 2011).

[12] JPC Merger Sub LLC v. Tricon Enters., Inc., 286 A.3d 1186 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. 2022).

[13] Id. at 1196–97.

[14] The figures in this article are based on the authors’ research.

[15] Cal. Civ. Code §§ 8122, 8124; see Wm. R. Clarke Corp. v. Safeco Ins. Co. of Am., 938 P.2d 372, 373 (Cal. 1997) (holding that pay-if-paid clauses are unenforceable because they unlawfully inhibit a subcontractor’s mechanic’s lien rights and are contrary to public policy).

[16] N.Y. Lien Law § 34; see W.-Fair Elec. Contractors v. Aetna Cas. & Sur. Co., 661 N.E.2d 967 (N.Y. 1995) (holding that pay-if-paid clauses are prohibited as against public policy).

[17] N.C. Gen. Stat. § 22C-2.

[18] S.C. Code Ann. § 29-6-230.

[19] Wis. Stat. § 779.135.

[20] Helix Elec. of Nev., LLC v. APCO Constr., Inc., 527 P.3d 958 (Nev. 2023) (citing APCO Constr., Inc. v. Zitting Bros. Constr., Inc., 473 P.3d 1021, 1024 (Nev. 2020)). However, the Nevada Supreme Court failed to clarify what pay-if-paid clause would be enforceable.

[21] See Va. Code Ann. §§ 2.2-4354, 11-4.6(B)(2).

[22] Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 149, § 29E(e).

[23] Del. Code Ann. tit. 6, § 3507.

[24] Gen. Ins. Co. of Am. v. City of Colorado Springs, 638 P.2d 752, 760 n.10 (Colo. 1981).

[25] Travelers Cas. & Sur. Co. of Am. v. Sweet’s Contracting, Inc., 450 S.W.3d 229 (Ark. 2014).

[26] St. Paul Fire & Marine Ins. Co. v. Ga. Interstate Elec. Co., 370 S.E.2d 829 (Ga. Ct. App. 1988).

[27] BMD Contractors, Inc v. Fid. & Deposit Co. of Md., 679 F.3d 643, 652 (7th Cir. 2012).

[28] Am. Erectors, Inc. v. Ohio Farmers Ins. Co., No. 09-cv-13424, 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 207090, at *25 (E.D. Mich. Jan. 13, 2012).

[29] Fixture Specialists, Inc. v. Glob. Constr., LLC, No. 07-5614(FLW), 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 27015 (D.N.J. Mar. 30, 2009).

[30] Sloan & Co. v. Liberty Mut. Ins. Co., 653 F.3d 175 (3d Cir. 2011).

[31] Wellington Power Corp. v. CNA Sur. Corp., 614 S.E.2d 680, 688 (W. Va. 2005).

[32] Cal. Civ. Code §§ 8122, 8124; see Wm. R. Clarke Corp. v. Safeco Ins. Co. of Am., 938 P.2d 372, 373 (Cal. 1997).

[33] 770 Ill. Comp. Stat. 60/21(e).

[34] N.Y. Gen. Oblig. Law § 5-322.1 (providing that a contract subject to payment bond rights cannot waive those rights and cannot make those rights subject to a condition); N.Y. Lien Law § 34.

[35] N.C. Gen. Stat. § 22C-2.

[36] S.C. Code Ann. § 29-6-230.

[37] Wis. Stat. § 779.135.

[38] La. Stat. Ann. § 38:2241(C); see also id. §§ 38:2247(A), 48:256.3(B)(1), 48:256.12(A). Notably, these changes were not made to the Louisiana Private Works Act, id. §§ 9:4801 et seq.

[39] Glencoe Educ. Found., Inc. v. Clerk of Ct. & Recorder of Mortgs. for Parish of St. Mary, 65 So. 3d 225 (La. Ct. App. 2011).

[40] Id.

[41] See, e.g., Minn. Stat. § 337.10; Mo. Rev. Stat. §§ 429.005, 431.183; Mont. Code Ann. § 28-2-723; Neb. Rev. Stat. § 45-1209(1); Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 4113.62.

[42] Wm. R. Clarke Corp. v. Safeco Ins. Co. of Am., 938 P.2d 372, 374 (Cal. 1997).

[43] N.J. Stat. Ann. § 2A:44A-38.

[44] Fixture Specialists, Inc. v. Glob. Constr., LLC, No. 07-5614(FLW), 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 27015 (D.N.J. Mar. 30, 2009).

[45] Id.